#5: Why can't I travel?

After being denied his right to leave Tunisia, the journalist finds himself facing a never-ending search for basic information about his case...

NOTE: This is a continuation of a previous episode. For full context, please read episode #1, #2, #3 and #4. If you’re reading the School of Tunisia for the first time, you can find an introduction to the page here.

On Thursday June 27th, 2024 - two days after learning at the Tunis airport that getting caught speaking with a black woman warrants a travel ban - I met with my lawyer on Avenue Habib Bourguiba in the center of Tunis. We had to pay a visit to the Ministry of Interior to find out what exactly this travel ban consisted of.

Avenue Habib Bourguiba is a strange place. What is supposed to be the beautiful, pulsing heart of the city is instead a securitized, militarized boulevard crawling with cops - both the uniformed ones and the discrete ones you start noticing with enough experience. Wifak once told me as we were walking there that she missed the avenue in the mid-2010s when it wasn’t yet a space of such paranoia.

At the end of the avenue stands the famous clocktower - a landmark that is to Tunis what the Eiffel Tower is to Paris. Across from it lies the infamous Ministry of Interior - a complete black box in Tunisia. What happens inside stays inside - just like it’s always been. Since the revolution, the number of metal fence rows in front of it multiplied and ate up more and more of the sidewalk. In 2022, perhaps in an attempt to make the Ministry look less evil, the authorities decided to swap the fences for a literal wall of large stacked empty flower pots made of stone.

Inside that large gray box of a building sit powerful men whose names are largely unknown to the public, making some of the most impactful decisions in Tunisia. Rumor has it, they do a great job making president Kais Saied believe he runs the show. Of course, rumors should be taken with a grain of salt.

My lawyer, Anas, and I met there - by the clocktower - at 9 a.m. As the police officer in the airport had instructed, we headed to the Office for Relations with the Citizen to find out what this travel ban was about. My travel ban was presumably based on a law that permits the issuance of a travel ban under specific circumstances and with specific conditions. But without knowing which exact judicial travel ban I was subjected to, there would be no way to address it and have it lifted.

In other words, without a physical paper confirming that a travel ban existed, there was just no way to have it removed.

The Office for Relations with the Citizen is situated with its entrance on the left side of the Ministry, away from the blocked-off main entrance. To enter, you walk through rows of fencing, quickly explain to an officer what you’re there for, then pass through a metal detector and a bag scanner.

Inside is a large, air-conditioned space with white walls and white-tiled floors. Office cubicles line the walls, and in the building’s center is a waiting area for civilians. Yet another electronic ticket machine is in use to keep the order of those waiting. The ticket numbers are displayed on a flatscreen TV next to a video that mixes action movie-like footage of special police forces on trainings with pictures honoring police 'martyrs' who died in various work capacities.

A big plaque announcing that the office’s establishment was financed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), as well as the British, Canadian and Japanese government, sits on the wall. From the ceiling hang inspirational banners in Arabic and French with slogans that promote the idea of the office bringing civilians and authorities closer together.

We waited for an hour or so before our number was finally called. We then walked over to the desk corresponding to our ticket. Anas showed his lawyer credentials and told the officer sitting behind his desk that he represents me and is seeking information regarding a travel ban. Then Anas told me to give the officer my passport.

“Chbih?” - “what’s with him?” - asked the officer, shrugging his shoulders with my still-closed passport in hand, invoking one of those expressions in Tunisian Arabic that are very hard to translate. The message was clear: “So what? I cannot be bothered dealing with this.”

The next step was to try the Administration for Foreigners and Borders, a specialized police station in the Montplaisir neighborhood. Knowing that Tunisian police stations tend to be more difficult to deal with the later in the day you show up, we hopped in a taxi and hurried over there. That police officer could have definitely given us the information, he just didn’t feel like doing the work. So much for bringing civilians and authorities together.

We arrived in Montplaisir 15 minutes later and entered the station there. We walked in the door and took an immediate left into a small waiting room with a long desk at the end where an older police officer in civilian attire was working. Anas announced our arrival, and we were told to take a seat.

We waited for another 15 minutes on the room’s green metal benches before we were called up by the older officer. Anas explained the situation to him, and he started making phone calls - first one to the airport and then another to the National Guard base in Laouina where I was interrogated a month prior.

After making his phone calls, the older officer told us that the travel ban came from the court in Sfax, but that he could not give us any information in writing. In order to gain more information, he told us, we would have to submit a written request for information at the Office for Relations with the Citizen. Yes - the office we just came from.

The request would take 7-10 calendar days to process, the older officer told us, and the information would then be sent to my lawyer’s office. With information on what law had been invoked to ban me from traveling, we would be able to move forward and challenge the ban in court.

With this newfound knowledge, we went on our way with the plan to make the request the following week.

Ammar 404: request for information could not be found

The following week, on Wednesday July 3rd, I got a message from Anas confirming that the request for information had been successfully submitted at the Office for Relations with the Citizen. Now we just had to wait. I updated my family, as well as the Danish honorary consul.

And wait we did. I was feeling ambivalent about it. It was nice that things seemed to be pretty straight forward. At the same time, I didn’t trust that the system would work as well as it theoretically should. But considering how things would evolve, it’s difficult to believe that I was simply the victim of a poorly functioning bureaucracy.

On July 12th, nine days after we submitted the request, Anas and I texted. That day was a Friday, so it seemed to be the last possible day within the 7-10 day window we had been given. Nothing.

July 13th, nothing. July 14th, nothing. July 15th, nothing. July 16th, nothing.

On July 17th - 14 days after we had submitted the request - Anas went back to the Office for Relations with the Citizen to inquire. They confirmed that they had received it and sent it to the Administration for Foreigners and Borders on July 4th. Anas went there to inquire.

After three hours of searching, the employees at the Administration for Foreigners and Borders said that the request had been lost. We had to start over and submit a new request.

Back to square one.

Two days later, on July 19th, Anas returned to the Office for Relations with the Citizen to submit a new request. Initially they refused to accept it, because their procedures require six months to have passed from the submission of the first request before a reminder can be submitted. But with minor changes to the request, he managed to submit it still.

That afternoon, I reached out to the Danish honorary consul, Leila, to update her on the situation. At this point, it had dawned on me that diplomacy getting involved would probably be necessary. Around 5:30 p.m., I texted her and requested a call.

I think my journal notes written that day capture well what was going on in my head, even if the language is not as polished as one might like. I wrote:

“The reason why I wanted to call was because at this point, I believed (and continue to believe) that there's a serious risk that these requests are lost on purpose to buy time for something or because they know the travel ban is illegal and don't want us to contest it. It was also pointed out to me that the courts will be out of session for most of August, which will probably complicate and delay the appeals process significantly at this point. Therefore, I wanted to get a sense of what exactly the actions are that the Danish authorities can take, and that's what I wanted to discuss with her.”

Being that it was the late afternoon on a Friday, Leila didn’t get back to me until Monday morning. Over the weekend, my parents wrote several unhappy messages encouraging me to be more stern with the Danish authorities. A note I wrote on Sunday, July 21st simultaneously captures how the situation was dragging out so much that it was becoming my everyday life instead of an exceptional situation, and how I was moderating my communication in order not to worry my family:

“I think that as I've normalized the situation more and more, I'm giving them [my parents] more details more casually, and it makes it feel more serious to them. But it has been a farce all along, not just now.”

Up until this point, I had still been clinging onto the hope that the Tunisian authorities would give up on this farcical persecution. But as the days passed without anything happening, my hope started to fade, and my anger toward the system grew.

In my thoughts, I kept returning to one question. If just gaining access to simple judicial information was this difficult, how much more difficult would it be to continue beyond that?

Getting the embassy involved

Early Monday morning, Leila called. I missed the call because I was sleeping in - part of my newfound routine that nicely complemented my slow spiral into hopelessness and depression. At 11 a.m., we managed to have a quick call, however, it was clear that she didn’t know exactly what Denmark could do to assist me. Being an honorary consul is a volunteer position after all, and Leila is a medical doctor by trade. I needed to discuss this with the embassy in Algiers.

That evening, on July 22nd, Leila sent an email to the team at the Danish embassy in Algiers, and an hour and a half later, I sent a follow-up with some clarifications and attached the submission receipts from the information requests. I also mentioned that I was considering bringing it to international media.

I understood well that my case was situated in the middle of the most vulnerable point of the Tunisia-EU migration cooperation. All the abuses that Tunisian security forces subject migrants to happen with European funding, training, equipment and encouragement. It’s easy for the EU to blame abuses on Tunisia’s kooky dictator and his racist rhetoric, but beyond the rhetoric lies the material reality: Just like Europe outsources its manufacturing and resource extraction to poorer countries where the workforce is paid less and has worse labor protections, it also outsources the human rights abuses necessitated by its migration policies to countries like Tunisia.

Even my own country, Denmark, has been part of financing two training facilities for Tunisian security forces in the past couple of years.

Unfortunately, my case, being the first known case of its type against a European citizen in Tunisia, reveals an uncomfortable truth. When European journalists attempt to understand what European money does in Tunisia, we get persecuted by European-funded and trained police forces in the service of a border regime that benefits no one but Europe (and its mercenaries).

It does not harmonize well with the grandiose European ideals of press freedom. For this reason, I also thought of keeping my story from the public as leverage. Neither the EU nor Tunisia would have an interest in my story being public - and in my opinion, it should lead to a questioning of the entire migration cooperation.

But to continue to the story. The vice-consul at the Embassy, Randi, responded to my email three days later, at 11 a.m. on July 25th. At that point, exactly one month had passed since I was blocked from leaving, and we still had no information on why and on what basis it happened.

It was a pretty vague email, prefacing that the embassy cannot normally affect an ongoing case in another country. I understood that there was a need to set realistic expectations. I also understood that from the embassy’s perspective, I was a Danish citizen in trouble in Tunisia who claimed to be a journalist and told his story from his perspective. At this point, they would have no way of knowing if I was being truthful.

Randi then offered to send the Tunisian foreign ministry a ‘note verbale’, which is a formal diplomatic message. In the message, they could formally request information about the status of my case and my travel ban. I hoped that if my lawyer and I could not get the information on our own, maybe my embassy could get it and share it with me. In that context, I couldn’t help but think how awful it must be to just be a regular Tunisian citizen with no embassy to turn to.

She emphasized that it might not advance the case and ended her email by saying that we should wait the 7-10 days on the second request before sending a note verbale. However, she had misunderstood what the 7-10 days of waiting were for, describing them as the “case processing time for processing a request for permission to leave Tunisia," rather than simply a request for basic judicial information.

18 minutes later, I replied to her email, noting the misunderstanding and making a point of emphasizing that there were no charges, and that I had never received any official information about a travel ban. In fact, had the cop in the airport passport control booth not accidentally stamped my passport and then re-stamped it with a cancel-stamp, I would not even have proof that I was denied travel.

In the email, I also wrote that I expect some level of Danish diplomatic engagement in this, and I explicitly voiced my fear that the Tunisian authorities were buying time to create a case against me on the basis of my journalistic work and/or statements I’ve made over the years on social media.

At 2 p.m., Randi responded asking if she should interpret my email as a confirmation of the note verbale. I conferred with my lawyer, then confirmed with Randi at 5 p.m.

Illegally travel banned

July 29th was a Monday and the 10th day of waiting on a response to the second request for information. The day before, my girlfriend and I had discussed my media strategy and come to the conclusion that I would begin to pitch international media to write about the situation if no information was dropped off at Anas’ office on day 10.

I was awake all night, anxious about the media strategy. I already felt paranoid and watched whenever I left the apartment, so the thought that my story would hit the media, and anyone on the streets would be able to know who I was and what I was going through felt extremely scary. In late July is when my new sleep pattern really kicked in. The new norm for me became a four-day cycle: three nights of barely sleeping followed by one night of passing out from exhaustion.

At 2:30 p.m., Anas texted. Nothing had arrived at his office, but he would return at 4 p.m. to check again.

“I'm willing to bet a lot of money that nothing will be there by 4 p.m.,” I wrote in my notes that day. And sure enough, nothing arrived.

I spoke with a friend who is a journalist and got the contact information for an editor at a well-known American media outlet. I’m not going to name names of outlets and editors with whom I was in touch over the following month, because it was a bad experience, and I’m afraid I won’t be able to get work as a freelancer again if I do.

Most ignored me, and a few politely declined. Two outlets responded with interest and wanted to set up a call, but one ghosted me when I suggested a time, and the other postponed our call once, then ghosted me on the day of the second call.

One final outlet’s editor sent my pitch email to one of his reporters who reached out saying that he was “deeply sorry,” and “was wondering if you want to have a chat on this soon.” I told him that I was happy to chat. But I also made sure to note that I had sent a pitch email because I am a full-time freelance journalist, it is my only income, and after close to three months with no work, I frankly needed both the pay and the byline.

Furthermore - and I didn’t say this in my email - I was nervous that another journalist might frame the story within a problematic context that could hurt my case.

I never heard from the reporter again.

I’m no stranger to the journalism industry. I know well that it’s a tough industry, and that many of those who make it to the top do so on the backs of others. Maybe I’m just not cut out for it. But even then, I don’t think it’s too much to ask of people who feel “deeply sorry” that they respond to emails, even if they take away from their dreams of breaking another story.

But back to Tunis.

The next day - July 30th - I sent a scan of my Tunisian residency card to Randi who then confirmed sending a note verbale to the Tunisian authorities. The Danish authorities would send quite a few notes verbales over the next months, but no one replied to any of them. In the afternoon, I met with my lawyer and talked through it all.

I figured the worst possible consequences would be deportation or that my residency renewal (scheduled for September) would be denied. Was I ready to face those consequences? To be honest, no. But I was also not ready to face being stuck there like I was with no end in sight. I was more ready to be thrown out than to continue being in that situation.

At least, if I were to be thrown out, it would be a judicial decision. My lawyer explained that if I were deported, it would be a decision that the Ministry of Interior would make in the Administrative Court, which implies that the decision could be challenged in an abuse of authority lawsuit. Thus, being thrown out would not be irreversable.

On Thursday August 8th, Anas went back to the Administration for Foreigners and Borders to inquire once again. On that day, it had been 20 days since we sent in the second request for information, 36 days since the first one and 44 days since I was denied my right to travel.

Again, they refused to give any information on paper, however, the information was relayed verbally.

“The travel ban was issued by the Public Prosecutor at the Court of Sfax I, and it is still in effect.”

The travel ban is based on the following legal passage:

“In the case of flagrante delicto [being caught red-handed] or urgency, the Public Prosecution shall issue a temporary, reasoned decision to ban travel for a maximum period of 15 days, with the provision regarding this decision that the ban is automatically lifted at the end of the aforementioned period.”

In other words, the travel ban should have been lifted automatically after 15 days. This was day 44, and an official was telling us it was still in effect. This was undoubtedly illegal.

As for the law, “case[s] of flagrante delicto or urgency” are not well-defined in Tunisian legislation, leaving it to the discretion of the public prosecutor to decide what they encompass.

The “reason,” required by the law, seemed to be “There’s an ongoing investigation,” with no further information.

Next step: going directly to the court in Sfax.

Back to Sfax

On August 14th, 2024, my lawyer went to Sfax to inquire about the travel ban directly at its alleged source. At this point, it had been 50 days since I was blocked from leaving Tunisia.

That day, Liweddine Friji, whom you might remember from #2: A day in court where he interrogated me in questionable ways, was on vacation. Anas met one of his colleagues who was surprised to hear about the situation.

He then checked with the clerk of the public prosecutor who maintains the travel ban registry at the court. They found no trace of the ban in the court’s registry.

My lawyer then spent a couple hours writing and submitting a written request to lift the travel ban, including a detailed explanation of the situation.

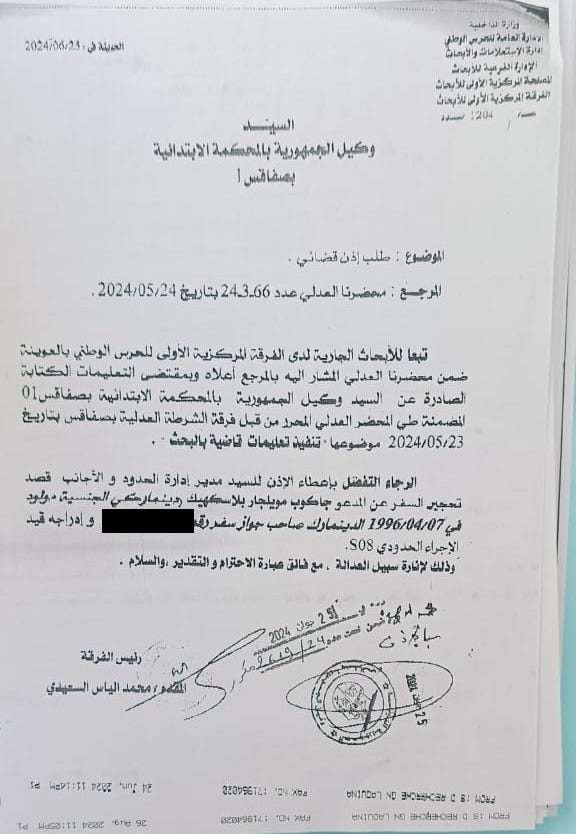

The office of the public prosecution then wrote a correspondence in a sealed envelope to the First Central Unit of the National Guard in Laouina, which investigated me, requesting a response and asking them to provide a copy of the travel ban decision, if it existed. That, along with my lawyer’s request, were placed in the envelope, and my lawyer would deliver it to the base in Laouina personally.

Anas explained that this was a legal order, meaning that the National Guard would be required to reach out and give an explanation. My hope was that since Anas delivered the note, he would not have to return to Sfax to hear the explanation but receive it at the National Guard base. Of course, they love to make life as difficult as they can for lawyers for people like me, so that did not happen.

I updated Leila and told her the newest finding, that the travel ban did not exist in the travel ban registry at the court in Sfax, and that every time we learned something new, it all felt increasingly suspicious. The day after, I also spoke with the Danish ambassador in Algiers, Katrine From Høyer. She informed me that there had been no response yet on the note verbale. She also told me they were trying to set up a meeting with the Tunisian embassy in Algeria, and that they’d be able to bring up my case during a consular trip to Tunisia in September.

On Friday August 16th, two days after his trip to Sfax, Anas delivered the sealed envelope with the court’s legal order and our request to have the travel ban lifted to the National Guard base in Laouina. Sadly, they refused to make the call on the spot and said they would make the call Monday or Tuesday.

Unfortunately, that meant we had to make the commute to Sfax again to get the information from the public prosecution.

Wednesday August 21st, Anas tried his luck going back to the National Guard base to ask for the information there. He waited for two hours, after which he was finally told that the chief of the unit was not there.

During these last few weeks of August, I was deeply depressed. I wasted my days away with no productivity, purposefully stayed up as late as possible in order to fall asleep more easily and had multiple emotional breakdowns in the midst of the inescapable paranoia. I could not even escape it in my own apartment where footsteps and voices in the building’s staircase set me off. Nothing seemed to work. The Tunisian system was broken, and even the media, which I had seen as my leverage in the situation, were irresponsive to a shocking degree.

And to make matters worse, my debit card expired at the end of July, so I had no access to any of my own money. I had been backed into a complete corner with no hope of anything working or changing.

Information at last

The following Tuesday, August 27th, Anas got a chance to do the three-hour drive back to Sfax to visit the public prosecution. I was unsurprised to hear that the National Guard investigative unit had not responded to the request from the public prosecution as they should have. After some back and forth, however, the public prosecution decided to reach out to the National Guard in Laouina by phone and get the information while my lawyer was present.

And finally, more than two months after being denied my right to travel, I was allowed to know on what basis my travel was denied.

That day, Anas learned that I was subjected to two concurrent travel bans: the S08 and the S17. The S08 is a judicial travel ban issued by the court on the basis of the above-quoted law. It should have been lifted automatically after 15 days, but it just was not. The S17 is more complicated.

The S17, also known as the ‘border consultation’, is an administrative measure within the Ministry of Interior. It did not come from the court system, and it is a verbal measure, so it has no paper trail. In essence, the S17 is an order for law enforcement to contact the Ministry of Interior directly when its subject shows up at an entry or exit-point (and sometimes also at routine stops within the country). Then the ministry makes an ad-hoc decision on whether to allow travel.

The measure was originally intended to prevent young Tunisians from traveling to Syria to join ISIS and has been criticized by human rights organizations and deemed illegal by Tunisia’s own Administrative Court. From what I understand, it is a new development that this type of order is used against journalists for covering migration.

The following day I received a copy of the request for the imposition of the travel ban. I was surprised to see that it was written on June 25th, 2024, and not on the day of my arrest. That means that when I was flagged in the airport in Tunis in late June and pulled aside, Elyess Saidi, chief of the unit in Laouina, began writing a request for a travel ban. He then sent it to Liweddine Friji in Sfax who approved it and returned it. That entire process took about three hours, after which I was told I was not allowed to travel.

The clerk in the court then entered the travel ban document into the travel ban registry. This was despite the fact that it had now been 63 days since the travel ban was issued on the basis of a law that requires it to be automatically lifted after 15 days. Yep…

On the bright side, a huge weight was lifted off my shoulders. I spoke with Anas in person a few days later, on August 31st, and he explained the next steps. Because finally, next steps existed!

The S08 should be simple enough. The request to have it removed had already been submitted, and the illegality of the continued enforcement of the order was indisputable. As for the S17, it required me to file a lawsuit against the Ministry of Interior for abuse of authority. The lawsuit is still going and - in case you’re reading along, person from the Tunisian Ministry of Interior - I intend to see it through.

Of course, these things are never as simple as they seem…

In the next episode of the School of Tunisia, fall is upon us, and I’ve finally received a bit of information and with it, a bit of hope. Yet, months seem to pass and nothing changes, as the Tunisian authorities continue to enforce an indisputably illegal travel ban…

If you found this post interesting and you’re interested in more, subscribe to this Substack to be alerted whenever the next post is published.