#3: "Welcome to the school of Tunisia"

The investigation reaches Tunisia's most specialized investigation unit, and once again, the journalist and the activist find themselves astounded that things have gone this far...

NOTE: This is a continuation of a previous episode. For full context, please read episode #1 and episode #2. If you’re reading the School of Tunisia for the first time, you can find an introduction to the page here.

That night, the exhaustion caught up with me. So after updating the Danish authorities, I fell asleep as soon as my head hit the pillow. Sadly, I continued to operate on a sleep deficit, as we were due to meet our two new lawyers the next morning at 7 a.m. in order to prepare for the third interrogation.

A bit past 7 a.m., my taxi arrived in Cité Urbain Nord. Wifak arrived on her own around the same time, and we walked into a building and up a few floors to the office space of our new lawyer. We went inside and sat down with the lawyers, Anas and Rania, to prepare as best we could.

Two days prior, on the day of our arrest, two of Wifak’s friends who are also activists had been interrogated at the base we were about to head to, and they had reported back a reasonably respectful experience. It was somewhat comforting to have a sense of what to expect. We discussed the case details with the lawyers, and they gave us the best advice a lawyer can give a client: keep your answers short and honest, and don’t give them answers to questions they aren’t asking.

Around 8:30 a.m., we left the office to go to the National Guard base for our 9 a.m. interrogation.

The Laouina National Guard base is the central base for the Tunisian National Guard, which is a branch of the internal security forces. While national guards in many countries are branches of the military that belong to defense ministries, in Tunisia, they are a (heavily militarized) branch of the Ministry of Interior. They function as police in rural, peri-urban and border areas, as well as on issues pertaining to borders like black market antique smuggling and migration.

Few people in Tunis have been inside the Laouina base. Most simply know it as the long white wall with the barbed wire that stretches along the highway between downtown Tunis and its affluent northern suburbs. At the center of that long stretch of wall is a tall green metal gate, topped by a majestic arch and flanked on each side by signs reading “the National Guard” in French and Arabic respectively. These days, sometimes an armored vehicle is parked out front for added effect.

We arrived in front of the base, entered through an entrance for civilians next to the main gate after presenting our convocation and passed through two sets of metal detectors and a bag scanner. Inside, we entered a well-maintained and air-conditioned waiting room, received a ticket from one of few ticket machines I’ve seen in Tunisia and sat down to wait for our turn.

After 15 minutes or so, our number was called. Wifak, our lawyers and I were led outside through a sliding door at the back of the room. A clean, white minibus pulled up, and we opened the door and hopped in.

Driving through the Laouina base was surreal. In the middle of the base was a huge grass lawn, well-maintained and with properly trimmed bushes and trees around. No trash was in sight - which, sadly, is a rarity in Tunisia. Several sprinklers were watering the lawn - also something I’ve never seen in Tunisia, other than at resort hotels.

“How crazy is it that I’ve ended up here, exclusively because I dared speak with a black woman?” I asked myself. I was terrified on the one hand. But on the other hand, as a journalist and researcher working on issues tied to policing, I was admittedly a bit excited too. I would get to see the belly of a beast that very few people get to see.

The base is a far cry from every police station and other public building I’ve seen in Tunisia. Judging by Google Maps, the base even has a full-size football field and multiple smaller sports fields, including a tennis court - more than can even be said about many of Tunis’ popular neighborhoods.

It was fascinating to see that Tunisia’s core-periphery dynamic extends even into the ranks of those enforcing it.

We drove to a far corner of the base and arrived at the building we would be interrogated in. Next to the building’s front door hung its inauguration plaque with Hichem Mechichi’s name on it. Mechichi was the Tunisian Head of Government and Minister of Interior until Kais Saied dismissed him on July 25th, 2021.

We entered the building and were seated in a small waiting room with light-blue walls, sterile lighting and a table in the middle with chairs around it. In the corner stood what seemed to be a broken coffee vending machine. Four middle-aged men were sitting together on the other side of the table discussing what must have been their own case.

Not much time passed before a man came to get Wifak, leaving me by myself. This was the first time we were going to be interrogated separately, it seemed.

While she was being interrogated, I sat in my chair staring at the wall and thinking; there wasn't really anything else I could do. Our lawyers were in the interrogation room with her, so I was alone with no phone, just sitting. I fiddled a bit with my shoelaces and tried to listen in on the conversations of the other group who seemed to be taken out one by one for interrogation as well - though much faster than us.

After what seemed like an hour and a half or so, a cop popped his head in the doorway. He looked at me:

“You speak… Sweden?” he asked.

I giggled in disbelief and told him:

“No, I speak English and Danish.”

He grunted and left.

More time passed and after what felt like a total of three or so hours, I started to notice some commotion in the building. I saw Anas pacing by the doorway to the waiting room speaking on the phone, which made me think that Wifak’s interrogation had ended.

Sure enough, after another 10-15 minutes, it was my turn, and I was taken out of the waiting room, to the right and down the hallway.

“Welcome to the school of Tunisia”

I was brought into a small office. The door opened to the right, and on the left were two desks standing side by side with a two-foot gap in between them. Three chairs were fitted in the tight space between the second desk and the wall on the right - one for me, and one for each of our lawyers. The first desk was mostly empty, but the second was overflowing with papers and binders, as well as a desktop computer that I cannot imagine would run an operating system newer than Windows XP. Behind the computer screen, on the edge of the table, sat a plate with a half-eaten piece of square catering cake. Presumably they had given it to Wifak during her interrogation.

Behind the desk sat a young man, Zaidi, perhaps in his early 30s, wearing a casual blue button-down shirt and rectangular glasses. His hair looked greasy and messy, and he stank of coffee and cigarettes. To me, he looked like a Computer Science PhD student who had just awoken from a nap.

Zaidi is an investigator with the First Central Unit of Investigations of the National Guard in Laouina, one of a handful of numbered central investigative units on the base that form the most advanced investigative units in Tunisia. They have access to the most advanced technology, apparently including the Israeli intelligence software, Cellebrite, as well as training and certifications abroad on how to use it.

These are also the units tasked with investigating high-profile political cases. For example, the case brought against Abir Moussi was investigated by Zaidi’s unit - the same that investigated me. Abir Moussi is the president of the Free Destourian Party and is currently in prison, sentenced under Decree 54 for disseminating fake news because of her public criticism of the Tunisian High Independent Authority for Elections.

We began the interrogation. My lawyer, Anas, told me that he would be translating during the interrogation - presumably because the unit had sought out a Swedish translator by mistake and failed to find a last-minute alternative. So the plan had become that Zaidi would ask Anas the questions in Tunisian Arabic, then Anas would ask me in English. I would respond in English to Anas and he would translate for Zaidi.

With the translation process and Zaidi writing everything into a statement on the computer, the interrogation went incredibly slowly. For the first while, we were going through formalities: my name, my parents’ names, my address and so on. Then another man entered the room, whom I later learned was the chief of the unit.

Elyess Saidi was slightly older, probably around 40 years old. He was a tall man with the body shape of someone who lifts heavy weights in the gym but also drinks too many beers on the weekend. He had slicked-back black hair and a beard, and he wore a white button-down shirt whose top three buttons were open, revealing a silver chain and a white undershirt. His look was straight out of the TV show Narcos.

Saidi came in and sat on the edge of the empty desk, listening in. After just a few minutes, he joined the interrogation, and from then on mostly took it over. Saidi spoke decent English, which made the interrogation more effective in the absence of a licensed translator.

The interrogation was significantly more professional than both the one in the police station in Sfax and the one in the court. Each question was asked once, with no aggression and ready acceptance of my answer. At no time did I feel like the victim of aggression or intimidation. While the bar was set pretty low during the previous two days, it was still nice to not acutely fear for my safety at all times of the interrogation.

We went through many of the same questions that I had already been asked in Sfax. Why was I in Sfax? How do I know Wifak? Who do I work for? What have I published? How did we meet Nelle, the Cameroonian woman? And so on and so forth.

Saidi then took out my passport, which I had given to them at the entrance, along with my Tunisian residency card. He looked through it. The passport had student visas for the U.S. and the UAE (I did my undergrad at NYU Abu Dhabi), as well as tourist stamps and visas from Senegal, Nepal, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Mexico and Morocco. Nepal and Mexico did not interest the interrogators, but the rest did. I told him that I had been a tourist in Senegal, Turkey and Saudi Arabia, and attended a conference in Morocco.

As for the student visas, I told them that I had done my master’s degree in the U.S. and my bachelor’s degree in the UAE. Saidi asked if I had studied at NYU in the UAE. I felt relief to know that I was speaking with a man who knew a bit about the world. In hindsight, he probably just searched up my name online before the interrogation.

“Did you ever serve in law enforcement in any country?” he asked.

“No.”

“Did you ever serve in the military in any country?”

“No.”

“Do you have any other citizenships?” Saidi asked.

“No, just Danish.”

Then Zaidi decided he wanted to know if I was Jewish. After asking the question in Arabic, Anas told him that he can ask the question if he wants, but that he should be aware that it is illegal to ask under Tunisian law. Zaidi and Saidi decided to pull the question back.

In hindsight, I wonder if it would have helped my case had I interrupted and clarified that I am not Jewish. It shouldn’t make a difference, but it might have made one anyway.

“Have you ever been to Israel?” Saidi asked.

“Yes,” I told him, “though I prefer to say I visited Palestine.”

In 2018, I spent a week as a tourist in Ramallah, Bethlehem and al-Khalil (/Hebron) in the West Bank, flying in and out of the airport in Tel Aviv. Needless to say, my politics have changed a lot since then: seeing the occupation in action in al-Khalil in particular led me to align with BDS. The statement produced during the interrogation accurately reflected my words and explanation of this.

Chief Saidi then asked me the first accusatory question of the interrogation.

“Why is your phone factory reset?”

Flustered, I looked at him and mumbled, “I don’t know.”

“Well, the phone arrived at my office this morning with nothing on it. You want us to write in the statement that you have no idea how that happened?” he asked.

While packing to head back to Tunis the evening prior, I had taken out my laptop and attempted to erase the phone remotely. Wifak, who previously worked on educating activists in cyber-security, informed me that if I had connected my Samsung phone to my Google account, I should be able to factory reset the phone from afar from my laptop. I attempted to erase it but received a message that it was offline and would be erased whenever it came online again.

I told this to Saidi, not realizing that he was probably referring to the manual deletion of most of my pictures and apps with sensitive information by the friend who was holding the phone while we were at the court, and not to an actual factory reset.

I told him that after the two previous rough days of aggressive interrogations, combined with a grand total of five or so hours of sleep, I was in a state of panic and wanted to protect my sources - a right protected by the Tunisian media law.

Saidi said that it’s not possible to delete the phone from afar like that, and asked me if I really wanted that as my explanation in the statement. But I was stuck on the wording of his question - “why is your phone factory reset?” - and was convinced that they must have turned my phone on, after which it automatically factory reset in response to my request the previous day.

“That’s what happened,” I told him, shrugging my shoulders in confusion.

At this point, several hours had passed in the slow-paced interrogation room. Their last line of questioning was about money. They asked me how I get paid in Tunisia for my work. I told them that I get paid via bank transfer.

“Is it a Tunisian or international account?” Saidi asked.

“I have one American account from my time there as a student, and one Danish account,” I responded, telling them that I use both.

They asked for both of my debit cards, took pictures of them, front and back, and kept them out of reach on the desk until the end of the interrogation. Undoubtedly, they noticed that the American card was slated to expire in June and the Danish one in July - which would end up causing major complications down the line.

At this point, Saidi and Zaidi were both losing their concentration, and a few other officers were rotating in and out of the office. I could tell that the interrogation was ending.

As if to conclude, Zaidi looked up and spoke directly to me in broken English.

“Welcome to school of Tunisia,” he said.

Gearing down

Saidi had left the office, and Zaidi started doing his own thing on the computer.

“Where was the ka7loucha from again?” he asked one of my lawyers, who responded that Nelle was Cameroonian. Ka7louch for a man and ka7loucha for a woman (كحلوش/ة) is a derogatory word for black people in Tunisian Arabic.

A third officer came into the room and asked me if I like Tunisian food, name-dropping kefteji and leblebi in anticipation. I repeated the words back, confirming that I do indeed enjoy these delicious foods.

“He speaks Arabic! He speaks Arabic!” Zaidi blurted out from behind his computer, as if he had discovered a damning secret.

“I live in Passage, of course I speak some Arabic,” I responded, referring to the neighborhood in central Tunis where I lived. “Stika ma,” I added, referencing how I’d use Arabic at my neighborhood corner store. Stika ma refers to a six-pack of large water bottles. Zaidi and the kefteji-officer chuckled.

After a bit, Zaidi left to go print out the statement and left me and my lawyers in the interrogation room with a random officer. He left the office door open, and I was able to look into a yard for smoking across the hallway from the office door and lock eyes with Wifak. I asked if I could leave the room and go out there, but the officer said no.

Another officer asked if I was hungry. My food intake over the past three days was limited to a sandwich and an omelette, so I was quick to say yes. He brought in two tiny tubs of vanilla-flavored yogurt and set them on the table in front of me.

I asked for a spoon, and an officer brought me one. Zaidi must’ve overheard this, because as I was eating my first spoonful from one of the tubs, he came in and grabbed the other.

“Look,” he told me. I watched in disbelief, as he ripped the plastic seal off the yogurt tub, knocked the tub back like a shot of liquor, and then proceeded to lick the seal exaggeratedly.

“The Tunisian way,” he said. I found it disgusting, but I faked a chuckle.

The statement was brought in, and we reviewed it. It was entirely in Arabic, but I went through it line by line with Saidi and my lawyers translating, and I do believe that it fully and fairly reflects my answers. I signed three separate copies of the statement.

After taking them to another room for a few minutes - I’m not sure why - I was handed back my bank cards. Then my passport and residency card. The atmosphere at this time was comfortable, and the lawyers and investigators were chatting. Perhaps it was a testament to the high degree of professionalism in the way they treated us, at least compared to your average Tunisian cops.

During these last few minutes, Saidi asked me:

“Do you have any questions for me?”

I thought about it for a second.

“If I meet a black woman in Tunisia in the future, is it okay for me to speak with her?”

“Yes,” he said.

Leaving Laouina

We left the interrogation room together and dropped by Chief Saidi’s office on our way out. Inside, he sat down behind his beautiful wooden desk with a golden name placard on top. While chatting with the lawyers and Wifak in Arabic, he brought up Mohamed Zouari, like Liweddine Friji had done in the court in Sfax the day before.

This time, it felt less like an overt threat, and more like an apologetic justification of why we had to go through this. Of course, almost seven more months of investigation would pass, and Saidi would personally write out a travel ban request against me a month later, as we will learn in next week’s episode. So in hindsight, I’m not quite sure if he was genuine or merely feigning concern in his office that afternoon.

Two months after my interrogation, Lieutenant Colonel Elyess Saidi was promoted.

On the way out of the building, I was told in passing that they worked really hard to get us out.

I came to understand that I had been waiting in the interrogation room because the police officers needed to brief the public prosecution in the court in Sfax over the phone. Based on the statement from the interrogation, which was faxed to Sfax, the public prosecution would decide what to do next in our case. I never confirmed it, but I understood the implication to be that it took serious work to keep us out of jail.

As we were sitting for a bit on a bench in front of the building waiting for the minibus to come back, I asked Rania, the lawyer, when we’d get our phones back. She insisted that once the case closed - maybe it would take a month or so, since there was no evidence of a crime - there would be a form to submit to retrieve the phone.

We left the Laouina base, and Wifak, Anas and I stood on the street chatting for a while, waiting for a friend in a car to show up. Wifak and I compared our interrogations, and I learned that they had been very different. While mine was straight forward - one question, one answer, and one sentence in the statement - Zaidi had asked Wifak the same questions repeatedly, presumably to try to catch her contradicting and incriminating herself.

When our friend arrived in his car, we drove to downtown Tunis and joined other friends at a bar.

I asked both Anas and Wifak a few times what would happen now, and I again came away with the impression that maybe a month or so would pass, and things would return to normal. But Anas’ main advice at this time was to be happy that we were free.

Clearly, I was on a different wavelength than everyone else at the bar - I imagine because far from every activist who enters the Laouina base gets out on the same day. So that in and of itself was worth celebrating. However, I was too tired and worried to celebrate, and I just wanted to know the meaning of what had just happened. I had a single beer and went home.

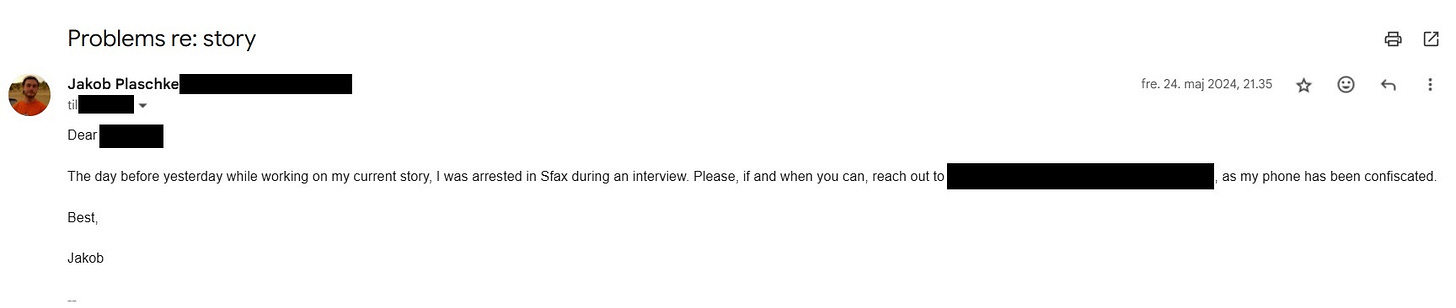

I’ve been considering for weeks if I should leave out the last part of my story from that Friday. Sadly, I remain nervous that coming off as an ‘unreasonable’ or ‘difficult-to-work-with’ freelancer may ruin my chances of getting work in the future. As an early-career journalist, burning bridges is costly. But I’ve concluded that this bridge is burnt already.

A few hours later, at home, I decided I better email my editor at the New Arab who had commissioned me to write the article I was working on when I was arrested: 900-1100 words for US$ 300 about migrant women giving birth under difficult circumstances in the hospital in Sfax. Since I no longer had my phone and didn’t know how much surveillance I was under, I asked the editor to reach out to a trusted friend via Signal.

Sadly, I never heard a word from my editor or from the New Arab again.

In the next episode of the School of Tunisia, it’s late June - about a month after the arrest. I try to travel to Denmark to renew my bank card and visit my family and friends, but I’m turned away at the airport. Several months of failed attempts to understand why follow…

If you found this post interesting and you’re interested in more, subscribe to this Substack to be alerted whenever the next post is published.