#2: A day in court

In a court in Sfax, a journalist and an activist find themselves faced with a calculator-wielding judge, throwing around theories of espionage...

NOTE: This is a continuation of a previous episode. For full context, please find the first episode here. If you’re reading the School of Tunisia for the first time, you can find an introduction to the page here.

Wednesday afternoon after arriving in Sfax, I had paid for a night in a bunk bed in a youth hostel. But when we all left the café around 3 a.m. after the night’s interrogation, I joined Wifak and a few friends at her apartment for the night. I set my alarm for 7 a.m., knowing that we’d have to appear at the police station at 9 - not that it mattered much, because the closest I got to sleep were a few short spells of delirium.

By 7 a.m., we were all awake, drinking coffee to combat our heavy under-eye bags and existential dread.

Afraid of what the day would bring, we left our phones and passwords with a friend before heading to the police station so that they could be factory reset if need be. We would have no use for them during the day anyway, and we feared that the police would take them when we showed up at the station, or raid the apartment while we were gone. We hugged whoever needed to be hugged, and we were off to the station.

Around 9 a.m. on the 23rd of May 2024, we walked through the entrance to the musty police station we had left just hours earlier. We continued upstairs to find the door of the judicial police - where we were meant to appear - but they had yet to show up for work. So we waited for another hour in the front hall.

When a few officers in civilian attire finally showed up, we were brought to their office upstairs and sat in a deep black leather couch in the corner of the room. We waited - what for? I have no idea.

At the far end of the office stood a bookshelf full of thick binders. Most binders had month, year and a place name written on their spines. Wifak noticed a particularly thick binder titled “February 2024 Jbeniana.” Jbeniana is one of the towns just north of Sfax where thousands of African migrants stay in impromptu tent camps, and where Nelle lost her baby in a National Guard attack.

Two police officers were in and out of the office, sitting down, chatting, hanging out. One of them reprimanded me for sitting with my legs crossed. The other sat cross-legged himself.

Without a phone for reference, it was difficult all day to maintain a sense of time. But it felt like we waited in that office for almost two hours before anything happened. Were we called in at 9 a.m. just to ensure we would have no time to rest or to consult our lawyer? Or were the cops just too lazy to get us moving? We will never know.

Off to the court

The officers told us it was time to go. Rather confusingly, they suggested that Wifak and I walk, and they’d take their car. It was difficult to understand why we had to appear at the police station in the first place rather than just show up to the court building directly. However, since neither of us knew the exact location of the court building, we were placed in the back of one of the officers’ early-2000s VW Golf, and we drove the short drive all together.

At the court building, we met our lawyer and walked through the corridors until we reached the door to the office of the First Deputy to the Public Prosecutor of the Sfax Court of First Instance, Liweddine Friji. While waiting outside his door for about 20 minutes, our lawyer reassured us once again that the judge would most likely just ask non-confrontational questions to clarify unclear aspects of the police report from the night before. That couldn’t have been further from the truth.

Wifak and I entered with the two cops. Our lawyer was not allowed to enter, which I found weird. But they all claimed that it’s normal practice in Sfax. I’ve since learned that we did indeed have the legal right to have a lawyer present.

It was a small quadratic office, with bookshelves all around and a window on the back wall. In front of it sat Liweddine Friji behind his desk, which dominated the space. Four chairs stood in front of the desk in pairs, facing each other and forming what felt like a small, square stage. The cops sat down on the chairs, and Wifak and I were instructed to stand on the ‘stage’, like a pair of naughty third graders about to be disciplined at their school principal’s office.

Friji, a young man, perhaps in his mid-30s with dark, slicked-back hair and the round glasses of a guy who fancies himself an intellectual, wore a white button-down shirt and a serious facial expression. Ironically, he has previously been involved in civil society advocacy for migrants’ rights, working with the Arab Institute for Human Rights and the UNHCR. He began what I would describe as another interrogation.

Rather than ask clarifying questions related to the police report, he asked me about my work: Who do you work for? How much do they pay you? I told him that I’m a freelancer so I work for different publications, and that the pay varies from assignment to assignment.

Already at this point, Friji’s attitude was confrontational, and he barely let me finish my sentences before asking the next question. It was clear that the narrative was predetermined, and nothing I said would change that - I was considered not a journalist but… Something or someone else.

He asked me how much I made on my last article, at which point I felt relieved. I knew that I made very little money, and I’d be able to prove it fairly easily if needed. I mistakenly assumed that more money and more luxury would be more suspicious to Friji.

I made US$ 250 on my last article, I told him.

“And how often do you publish one?”

“It depends, but this past month, I wrote two,” I responded.

I was stunned by his reaction.

“It doesn’t make sense for you to be in Tunisia, working for this kind of money,” he told me. He addressed Wifak and the police officers in a mix of Arabic and French, somewhat agitated and repeating the word, “illogique” - illogical. It was not only distracting and confusing to be interrupted like this, but also disrespectful and infantilizing. I truly was the naughty third grader, standing at attention in front of the principal on his throne of self-importance.

He asked me if I live with anyone. I told him I live with my girlfriend. Is she Tunisian? No, she’s American. Where does she work? How much does she make?

I won’t be diving too much into the details here for the sake of her privacy, but in the Tunisian context, her income is solidly middle class, though it is a fraction of what expats paid in foreign currencies in Tunisia make. In central Tunis where we lived, that was sufficient to maintain a pretty decent lifestyle. “Illogique” once again.

Like a vendor in Tunis’ Medina trying to justify selling a magnet to a German tourist for 20 euros, Friji pulled out a large square calculator from his desk. How much do you spend on rent? How much do you spend on food? He asked aggressively, while punching in numbers on the little device. “Illogique, illogique, illogique.”

Before reaching any sort of finalized amount on his calculator - which, for the record, would’ve been within our budget, had he finished - he moved on to the next question.

“Why, when you have a Master’s degree, are you a freelancer?”

I tried to explain to him that it’s fairly common for journalists to start out as freelancers, build a portfolio, and then get a steady job later in their career, but he cut me off before finishing the explanation.

“It does not make sense to be a freelancer when you have a Master’s degree. Freelancing is only for people with no degree,” he concluded without letting me respond.

He then asked me, why, when I have a degree from the U.S., did I not just get a good job and stay there? I told him that even if I wanted to stay in the U.S. after graduation, I would need a visa.

“That’s easy for a European with a degree from there,” he said.

I told him that that is simply not correct.

I would’ve explained the H-1B visa lottery to him if he had let me. But again, he cut me off and told me, “it’s easy, I have friends who have done it,” and concluded that I was lying.

Once again, he did not allow me to talk any further.

And regardless, even if I could’ve stayed in the U.S., I was not looking for a well-paid office job - my passions laid elsewhere. But unfortunately in Friji’s head, it seemed that passion takes the back seat to monetary gain. Naturally, that prompts some questions about Friji’s own reasons for getting involved with civil society advocacy.

About two months later, Friji went on vacation and came back to a promotion. He now works at the Court of Appeals.

As the interrogation was ending, Friji turned to Wifak and addressed her. “Have you heard of the case of Mohamed Zouari?”

Wifak nodded.

Mohamed Zouari, a Tunisian aerospace engineer, headed Hamas’ drone program until his death. In 2016, he was assassinated close to his home in Sfax. From what I gathered in the court, in my National Guard interrogation the following day and online after the interrogations, he was assassinated by a group of ‘journalists’, and the investigation by the Tunisian authorities concluded that it was the work of the Israeli intelligence agency, Mossad.

“You know there was a Tunisian girl helping them?” asked Friji without expecting an answer, referring to the journalists’ fixer. “You know what happened to her? She got five years in prison,” he finished.

Further escalation…

After an excruciatingly long half hour, the interrogation ended, and the door to the office opened. Our lawyer joined us for a short exchange of pleasantries, after which we left Friji and walked to a large, noisy waiting hall full of people.

During the entire 30 minutes or so the interrogation had lasted, I felt like I had been dissociating. The discrepancy between the expected professional and educated exchange that would add some sense to the cops’ conspiracy theories, and the confrontational and leading monologue-adjacent spectacle I was subjected to, was just so absurd.

Already then, sitting in the waiting hall, I felt like I had just woken up from a bad dream.

We waited for what felt like several hours in the hall. Five or six of Wifak’s friends joined us there for a bit, but the plainclothes cops from the morning who apparently were still watching us eventually told them to leave.

After a while, our lawyer came and informed us that Liweddine Friji did not want to make the decision himself and had forwarded his materials from the interrogation to the public prosecutor himself, who would decide on the next steps.

The time in the waiting hall was nerve-wracking. What was meant to be the day during which everything was sorted, during which it would be made clear that it is not illegal to give a media platform to a black migrant in Tunisia, was becoming suspiciously long. I was becoming more and more afraid of what that signified.

Eventually our lawyer came back with a decision from the public prosecutor: he was opening an investigation into Wifak and me with a specialized investigative unit belonging to the National Guard in Tunis, and he issued a warrant for our phones and SIM-cards.

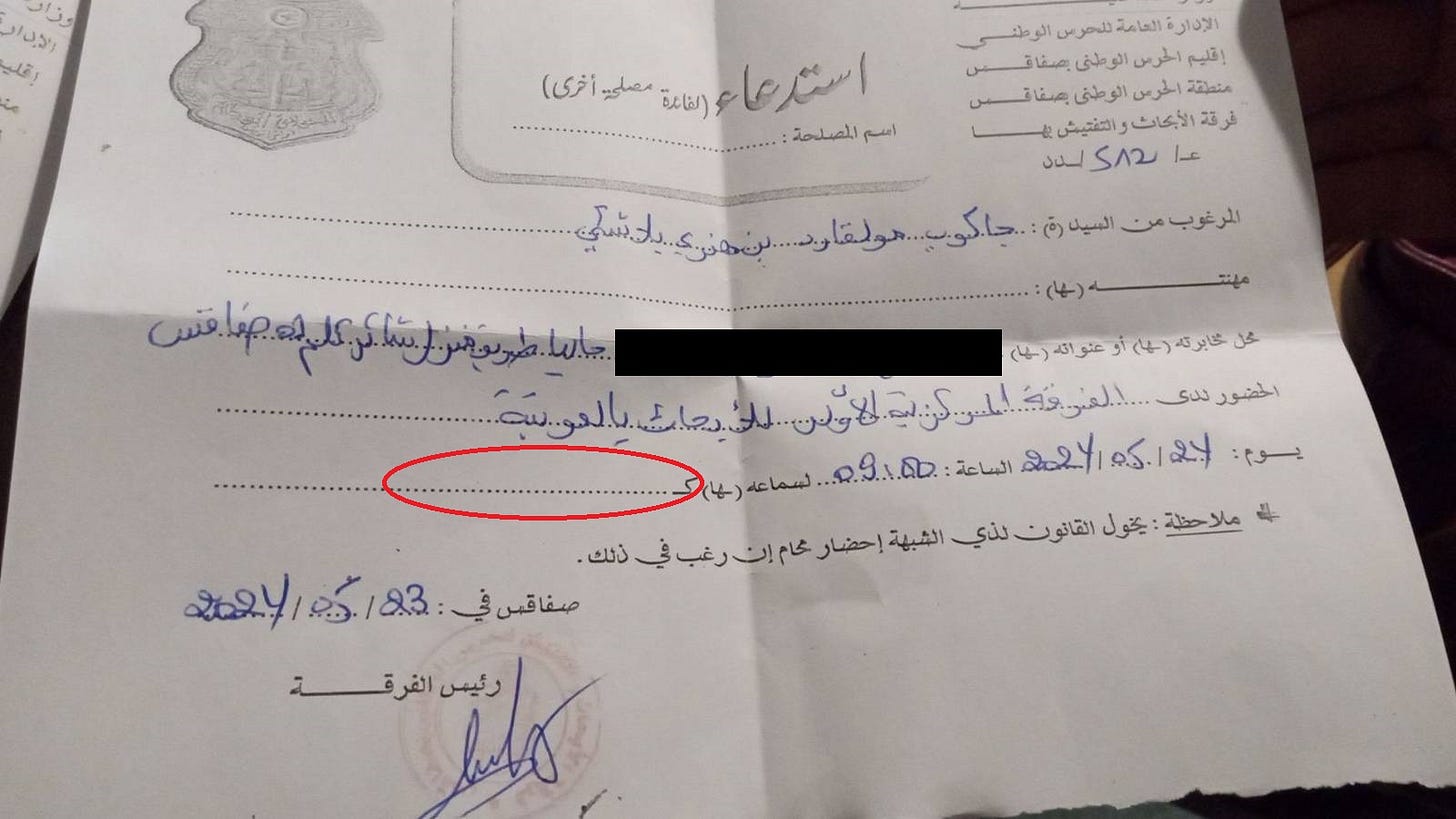

Furthermore, we were required to show up for interrogation at the National Guard base in Tunis (a three hour drive away) the following morning at 9 a.m. We were each given a convocation that, in violation of Tunisian law, failed to specify why we were summoned for interrogation. Thus, we still had no idea if we were suspected of committing a crime and no ability to prepare our defense.

The plainclothes officers asked us to hand over our phones, but of course, we didn’t have them with us. So the officers went out to get them. How? I have no clue.

Meanwhile, we were taken out of the court building and across the courtyard into another building. A staircase led us up many floors, after which we were seated on a bench rack bolted to the wall in a small hallway which seemed to be part of a court police station of some sort. Across the hallway, which was so narrow that I had to move my legs out of the way when a cop passed through, was a barred window overlooking the courtyard.

This is when it really dawned on me how serious the situation was. Our phones were being taken, and we had just been referred to Tunisia’s most advanced investigation unit - all because we dared speak with a black woman.

I had an emotional breakdown. I felt trapped in my own body, like it needed to burst open so that I could leave it. I started crying quietly but uncontrollably, as I was moving back and forth between sitting on the seat rack and standing at the window. When I sat down, I felt a desperate need for fresh air. But when I breathed fresh air at the open window, it made no difference.

For the first while, Wifak and I sat together and were able to chat and support each other. But after a bit, a police officer came and commanded her to move further down the hallway so we couldn’t communicate.

What felt like another couple of hours passed in that hallway, before a group of cops came in the door carrying our phones. They requested our pin codes. I would’ve loved to refuse to give mine up, but with the warrant from the judge, I assumed I was required to comply.

They called for me again 10 minutes later because my app lock had activated when they tried to open my messages. I had an app lock to add extra protection to apps I used for communicating with and storing data from my sources.

The app lock app itself was disguised as a calculator, and the officers couldn’t locate it, so they handed me the phone to disable it. With my phone in hand for the last time, I was happy to find that much of my data had been scrubbed before the cops were able to retrieve it. I had feared that this seizure would compromise the safety of my sources and contacts.

I disabled the app lock and left my phone with the cops in their office.

They let us go fairly quickly after that, and we went back to Wifak’s apartment to debrief, update our friends and my girlfriend through Wifak’s spare phone, and pack. At that point, the sun was nearly setting, and we needed to get back to Tunis that evening in order to make it to the interrogation the next morning.

We did what we had to do, packed up our things and got on a shared taxi - known as a ‘louage’ - to Tunis. In the afternoon, my girlfriend had called a hotline for Danes in trouble abroad maintained by the Danish Foreign Ministry and informed them of my situation.

Meanwhile, word had spread, and a friend from university who works in human rights advocacy in the U.S. had heard that I was in trouble. He managed to connect me with the right contacts at the Danish embassy in Algeria (which covers both Algeria and Tunisia).

I got home around 11 p.m. and finally got to have my first meal of the day. I stayed up a while longer to recount the past two days’ traumatic events to my girlfriend, as well as the ministry hotline and my embassy. It was not a fun day.

In the next episode of the School of Tunisia, we enter the infamous Laouina National Guard base in Tunis for an interrogation with one of the most advanced and politically-involved investigation units in Tunisia. In this crown of the tree, cynical political acumen is substituted for the unhinged conspiracy-thinking that characterizes the root system below.

If you found this post interesting and you’re interested in more, subscribe to this Substack to be alerted whenever the next post is published.