Nelle's story: Part 1

Nelle, the Cameroonian migrant woman, tells the first part of her story: Fleeing tear gas, sleeping out in the open and being intercepted at sea by the Tunisian National Guard, all while pregnant.

NOTE: This post exists in the context of a larger story-line. For full context, please find the main episodes here about my seven months being persecuted in Tunisia because of my journalism. If you’re reading the School of Tunisia for the first time, you can find an introduction to the page here.

This week, in anticipation of the final post in the series that chronicles my seven months trapped in Tunisia, we’re headed back to the very beginning. Why was I arrested in the first place? It’s a great question. And if anyone has the ability to get an answer out of the Tunisian authorities, I’d love to hear it. Because they would not give me one.

The answer I derived from my own experience, however, is that the Tunisian authorities do not want the world to know what black African migrants in Sfax are experiencing. In this case, they drew the line at the Cameroonian woman, Nelle, whom I was interviewing when we were arrested.

However, that won’t stop me from sharing the interview. I’ve therefore decided that this week’s post on the School of Tunisia will consist of long excerpts from my interview with Nelle. This is part 1 of the interview - part 2 will come at a later time.

Her story is a long one, and a trigger warning is appropriate given its treatment of topics of grim violence.

The interview was conducted on the evening of May 22nd, 2024, in Sfax, Tunisia, and I still retain the audio recording which, surprisingly, the Tunisian police never thought to inquire about.

The recording is all in French, so the below excerpts are translated. The individual parts below are all in the same order as when we did the interview. Whenever there are gaps in the interview, sometimes because I cut parts out for the sake of brevity, and other times because the wind made the recording unintelligible, parts are separated by an ellipsis. All parts of the interview are written with a quote-line on the left page margin. From time to time, I add small comments and clarifications, during which I’ve removed the quote-line.

I am Nelle, it’s a pseudonym. Because, well… but I prefer Nelle. Nelle, yes. I am Nelle, of Cameroonian nationality, and I am in Tunisia in order to cross illegally.

…

It’s been eight months [that I’ve been in Tunisia], I think. I arrived on September 27, 2023.

…

When I arrived, I first went to Tunis. After Tunis, a person took me because I had a luggage for a lady, and I was going to bring it to her, 23 kilos. So I went to bring her it. Then he [the person bringing me] took us back to his place. It was the older brother of a friend, so I trusted him, but when we arrived I felt that his behavior was a bit unpleasant.

The next morning, I decided to leave with the girl I had arrived with, because I arrived there with a girl. He didn’t want to see [/house] the girl unless he could have her for himself. I refused. I said she’s my responsibility, so I left through the girl’s network. When we then left through her network, a gentleman who was ready to take in the girl asked for us to come to Sfax.

Very early the next day, I took the girl, asked how much [for a ticket] to Sfax to see the gentleman. He was a Guinean. We arrived at his place, and he took us in without a problem and took care of us. Three days later, the girl’s brother was attempting [to migrate]. He was in the olive fields, at kilometer 19. He asked of the Guinean to bring us to the edge of the town.

Sfax has a peculiar circular city structure in which all the main roads start in the city center and move outwards. Locations within and around Sfax are primarily described by the number of kilometers away from the center they are located. The olive fields where migrants are camping out are mostly on the coastal roads north of Sfax, starting around kilometer 19 and continuing until around kilometer 35-40.

He refused because he wanted to keep us. But her brother had already brought together three convoys [boats]. And we didn’t want to wait. It would be better if we came out to the village there, things would be more clear [he said].

So the next day, he [the Guinean] accepted to let us leave. We just had to pay for the stay, so he asked us for I think 100 euros - 50 euros per person. Then we left for kilometer 19.

Arriving at kilometer 19, we arrived at the man’s place. In the olive fields in this period, it was free. There was an air of freedom. That is where we discovered the reality.

We started to sleep in the olive fields, as they found another spot for us. We stayed in the olive fields in order to be in a place where people normally travel [migrate] from. That was also at kilometer 19.

So we stayed there for about -from September to December. At that time, it was a bit difficult to cross because there was a lot of police. So we waited.

In December, while I was pregnant, and I was the only one who knew because I had a bit of trouble with the [fetal] growth, I began to bleed, because I ate dates. Only eating dates is what created all these problems. I was eating dates, and it affected my stomach and made me bleed.

I bled for about a week, telling myself that it would stop, but it continued. I didn’t think to take anything [medication], I just stayed calm and took some rest.

One morning, I got up, and it was like water. As I was standing there, it was like a pocket of water that went down. This was at 3 in the night.

So I got up at 3 a.m., and I went over to see the man who got us there, to tell him that I’m not okay at all, and that I didn’t have any money. I asked if I could borrow a bit of money so that I could go to the hospital, because this wasn’t going well at all. I was sure it was the child coming, that’s what I thought to myself when the water went down.

He said no, wait for the morning, it’s 3 a.m. I told him no. He didn’t understand what the water pocket thing meant. He gave me 40 dinars.

I waited until 4 a.m. and went all by myself. I didn’t want to invite the girl who stayed with me because I didn’t want her to take the risk. So I went all by myself.

There weren’t many taxis, so I walked from 4 a.m. until around 5:30 a.m., when I found someone else also looking for a taxi. Then we walked together and found a taxi around 6 a.m.

The taxi picked us up, and I said I wanted to go to the hospital. When I arrived there [at the hospital], it was around 7:30 a.m. I explained my problem, that my water broke, and that I’m pregnant. The lady there told me to take a seat. I stayed there, waiting, waiting, waiting, 8 a.m., 9 a.m., and they started cleaning. But no one received me.

I began crying, thinking: What kind of place is this? You arrive, you tell them your water broke, and they leave you sitting there for two hours? I just cried, cried, and cried.

The cleaning lady began asking me, “but why are you crying ma’am?”

I told her, “because I’m about to lose my child, and I’m seeing that no one cares about me.”

She said, “ma’am, do you have any children?”

I said yes.

“How many children do you have?”

“I have three children.”

She said, “wow, you’ve had a lot of chances.”

At that moment, her cleaning staff colleague started talking about trying to have children, going on and on about how she didn’t manage to have one.

You think that all children are the same, or you think that my stomach just grows, and then it happens? Even if I had 50 children, they would all be my children. I’m not like you who sees a lot of children there as if they were objects.

Anyways, they tried to calm me down, and there were also other Tunisian women there waiting because they were there for treatment. There was no sense of urgency in the air.

Then another one came to me and tried to calm me, telling me not to cry anymore and offering water and tea. I told her I didn’t want it. She offered me all sorts of things, in fact, even coffee. I just wanted someone to take care of me [medically].

It was at 10 a.m., and I had been there since 7 a.m. At 10 a.m. someone came to ask me some questions about my health, first about my identity and then about my health. When I explained, she left, and another stayed who was a bit more friendly. This one had me do an ultrasound. She said it was okay, it wasn’t my water that broke.

She had me do a blood test to find my blood type, but I already knew my blood type, so why do we have to do a test? She said it’s important to know it for certain. I told her that my blood type is O-positive.

She took me to another lady who told me I had to do the payment, but I told her I don’t have any money. She told me that it wasn’t her problem that I don’t have money. I asked her, if I’m going to get medicine, how will I do it if I don’t have any money?

She prescribed me three medications. I did some research and found that the first one was to stop the baby from coming out, the second was a painkiller, and the third was a medication for infections. So that means that the water loss could have been from an infection.

Back to the Zeitouns

Anyways, I went back [to the olive field camp], and everything was going fine. I continued taking the medicine. Everything went well, and I even got some of my spark back.

In order to better understand the scenery in which all of this is taking place, I will be adding a bit of explanation, with satellite imagery, all taken from Google Maps.

First, a satellite photo of Sfax and its surroundings. Kilometer 19 is marked with a black circle, and the main road relevant to the camp is drawn up next to the circle in red.

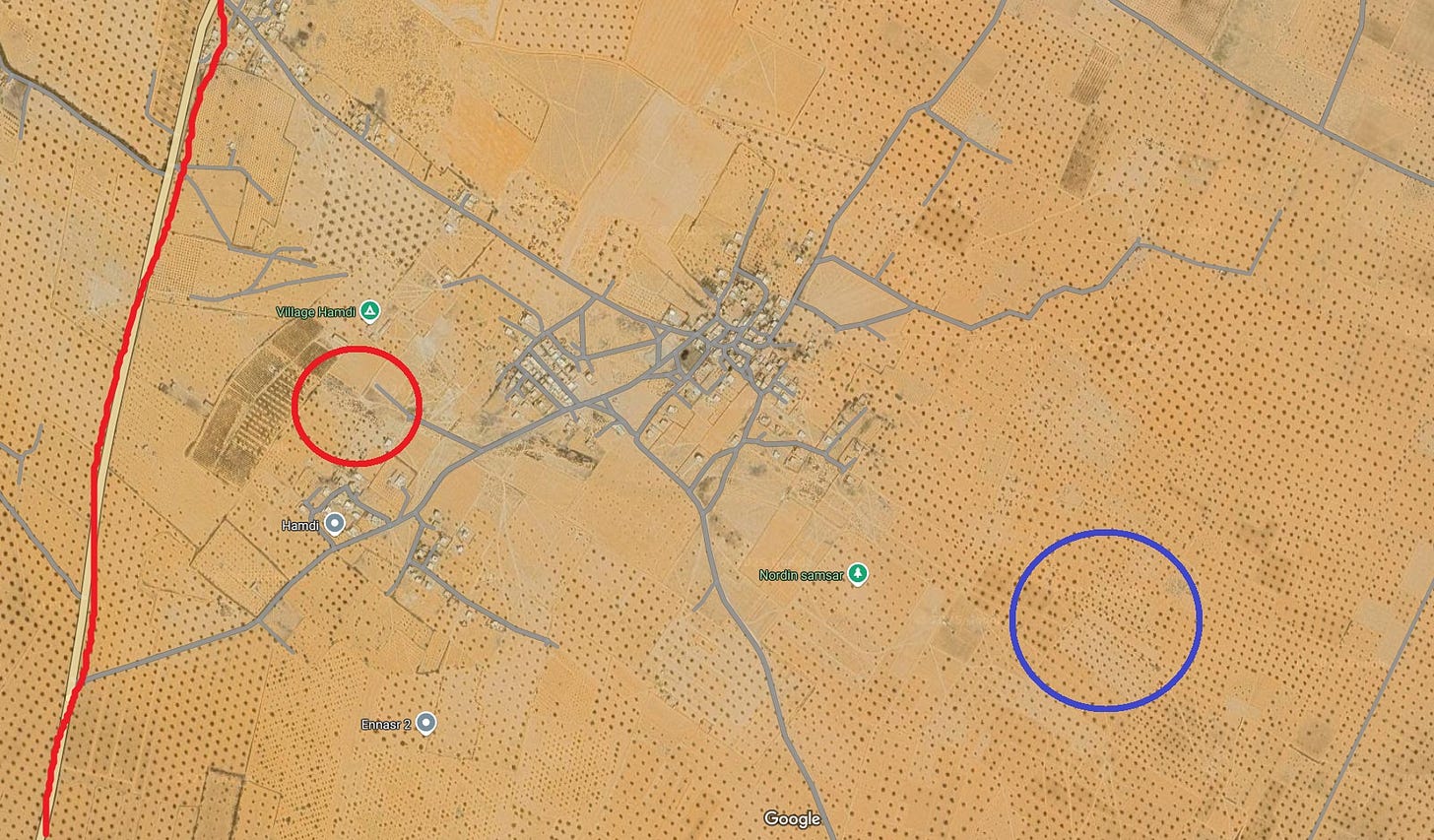

Second, a satellite photo of the area by kilometer 19 where the tent camps Nelle is staying in are located. I’ve marked the main road in red again. I’ve also marked a red circle and a blue circle, which locate two different clusters of tent camps that correspond with the following satellite imagery. The two clusters are two of many in kilometer 19. I’m sharing them in order to give a sense of the geographical size of the area, differences in camp density and what it means when the police head off the main road to attack one camp or another. I think it illustrates the scattered nature of the camps well, which is important in order to follow the narrative.

The camp circled in red is closer to the main road and has a high density of tents.

The blue area is much further from the main road, and the tents there are more scattered. Many of the large swaths of olive fields north of Sfax are dotted by low-density camp sites like this one.

Unfortunately, I was staying in the olive fields. One day around noon, people were just there, chatting and hanging out, and someone came over saying, “it’s over, it’s over, it’s over.”

“What’s going on?” they asked him.

“Oh, the blacks burned a police car.”

Shit. It was at this moment that everyone started putting on their shoes, realizing that this was a bad place to be in. And the police were apparently out [with their cars]. I didn’t know what had happened. I wasn’t there. Someone told me on the way there that it wasn’t good.

We got there around 1 p.m. There was one of our guys who went out to the road trying to look, because sometimes when things aren’t going well, we send someone out to the road to see where exactly they [the police] are going. He sent back a red alert.

Red alert. It was a way to tell us we had to leave, because the police would arrive that day with their war tanks, as if it was a war. It would be really, really, really bad there. They come with everything they need to wage a war. They bring all that.

They were coming, and I learned that they were arriving. They were bringing teargas, then they started shooting the tear gas, “boom, boom, boom.”

People were fleeing to our side [of the camp] because we were really in the back. That’s when I started running. I was running with the girl, we were always together, we ran and ran. We ran, not even knowing where we were going, just anywhere. You just follow and try to stay from the rain of tear gas, to anywhere. But I didn’t smell the odor there, because I was quick enough to get away before it came.

We returned around 6 p.m., we thought they were all gone, but they weren’t all gone. There were some [police] left that were circling the town. So they were still there.

…

At five o’clock the next morning, they returned to assault us and make us flee, then return later. Same thing. People hadn’t even settled in yet since the day before. That next day when they arrived at five, it was death.

As some were leaving for the other side [of the camp], others were saying no, they were leaving for this side. We left the Ivorians there who were saying “no, we’re staying, they didn’t do anything to us.”

I told them, “They didn’t do anything to you because they didn’t have enough cars to take you on. Stay there today and you will see.”

I took the hand of the girl and left, because I didn’t want to die sitting there. If I was at least running when they got me, that’s fine. I said [to those staying], “fine, don’t go then.”

…

They [the police] sent a couple of Tunisians who told us to “come down” [French “descendre”].

The couple came to us with hand gestures like this, as if they wanted us to come over to them. So, as if these men would see [and engage with] us if we came forward, everyone came over. Even I came forward with the one difference being that I still expected we’d have to do as previously, because the gas would be coming, and it came and came and came. And I shouldn’t breathe in the odor because I had to take care of my health.

I ran, and I just went straight forward. I went with the girl, and we ran, ran, ran, ran, ran, ran. At one point, I was crossing [a road], and bump, I saw a [police] car. I turned and ran away from the car to make sure they wouldn’t beat me, and I continued, but the car kept going.

I crossed the road there, and I was a bit uncertain because there was a small police shack by the sea. I didn’t even know where I was any longer.

I stayed there for a while [hiding behind a cover] and saw the police come by in a line.

…

I began to run fast. There was a police man that came out from where I had come from. I came out from where I was [hiding], because there was a man just meters away. I saw how the police officers, even they themselves didn’t know what was going on there.

I went back and when I arrived, I was fatigued.

The police cars were away, so it gave us a chance to breathe. [Before this moment,] You ran somewhere, the cars would come. You ran somewhere else, the cars would come there. They made us run in every sense of the word.

I stayed there and started to reflect, thinking no. If I run here, I will see police cars. If I run there, I will see police cars. I see people running and running all over, so I decided instead to find a place to stay still and hide myself.

So I left, I chose a place in which I could hide, and I ran there. They continued to whoosh, whoosh, whoosh [emulating the sound of tear gas grenades flying through the air above]. I hid.

…

[In the evening,] we left and returned to the olive fields. We went back and continued to stay there.

In December, I stayed there. It was becoming difficult. We couldn’t live... it was no longer calm. I have never lived a situation like that. The police, every day, every day, now they came every day. They came exactly to where we were. They came with all their pick-up trucks, right where we were staying.

Our guys called it “tennis,” they always had these ideas. Our cover as well, we called it Kosovo. Because even if you found yourself in the middle of it [the chaos], you could cover yourself.

They always came like this with the pick-ups, and the [Cameroonian] guys were wondering. We were observing. Because we didn’t run like the West Africans, they always run everywhere without thinking. We were watching, counting the number of pick-ups that came in, seeing what they were doing and everything. Sometimes they came, searching, searching, searching, boats, searching, searching, searching.

At a certain moment, they told the truth that in fact, they were searching for a firearm. During the attack, they had lost a firearm belonging to, I believe, a police officer who was injured, and then someone took his gun. And what happened then, I’m not sure.

They were telling us, “We want the firearm, nothing else. If you find us the firearm, we will leave you in peace.”

Then, the guys themselves started saying that we would find them the firearm.

We couldn’t even go pee because as if we were under the sword, we were afraid that maybe we’d go pee, and people would think we were digging to bury or unearth something. We were there like that, like we were frozen still.

One morning, they came with the photo of a small guy saying that he was the one who had the gun. The small guy, when we saw the photo, there was one Cameroonian who recognized the small guy. When he recognized the guy, he immediately began to look for him, because this little guy was staying in a little shack belonging to the ‘mbanga’ smokers here.

Mbanga is a Cameroonian slang word for cannabis.

They arrested him there. It was a Cameroonian who called, and then delivered him [to the police].

The next day, they came back with a photo of a girl. We saw the girl, and it was someone who came from Cote d’Ivoire. She had a photo online with two machetes like this [signals two crossed machetes]. We searched for the girl, but I’m not sure if they ever found her.

Then they returned with... They came back telling us that they were going to search the Arabs’ houses now. That’s when the Arabs started to make trouble there. They searched all the Arabs’ houses, but they didn’t find anything.

The “Arabs” in this context refers to the local Tunisians who live in the area, as opposed to the camped out migrants from other African countries.

Then they went walking around the olive fields searching for young guys. Now they were showing pictures of young Arabs whom they were searching for. We noticed that one of them was living there [in the area], but he was missing. When they came two days later to search the houses of the Arabs, they had hidden the weapon somewhere in the same area. The weapon was spotted a few times in kilometer 19, I’m not sure exactly where. But I was told that at one point, it was spotted in kilometer 19, and a guy called the police when he saw the firearm.

The police came and took the weapon, and thanked the guys and all. Then, as they had said, if we found the weapon, they would leave us in peace, so we thought that it was over.

But that was the moment that the real war began.

Boom, boom, boom, boom, kilometer 24, in all the camps in the olive fields they were now shooting tear gas everywhere, attacking now, arresting people. It became the real war of shit.

I started to say to myself, “Shit, what have I gotten myself into?” And with the growth [of the baby]. What will I do in this country?

…

After about three months in the olive fields, in kilometer 19, I knew I needed to change things, because I was crying every day.

…

Then there was a lady who told me a boat was leaving from kilometer 34 that would leave tomorrow, Monday. So I left where I was and went to kilometer 34. I left my group and went to kilometer 34 in December. I left with an Ivorian.

We left around 4 or 5 a.m., walking from kilometer 19 to 34 on foot. When we arrived, I was so tired. Then God sent me a sign. They said no, the Arab [organizer of the attempt to cross] has said that he won’t take more than 45 [people].

So 45, then, alright. They told me that I couldn’t come any longer. Crying, tired, they said don’t cry. When it comes to crossings, don’t cry, you shouldn’t cry.

You made me come, you knew the distance I had to walk to get here just to hear that I can no longer come.

“No, you can wait for the next group,” [they told me].

I said, “if I was going to wait for the next group, I would wait in my other group [at kilometer 19], why did you bring me here?”

They said, “tomorrow we will see how we can fit you in the vehicle.”

I accepted that and to stay overnight, and I slept in the open air.

The next day, they came to me and told me that there was a girl who had left, and I would replace the girl. That’s how I ended up staying. In the end, they didn’t leave [attempt to migrate] anyway, and I waited and waited and waited for two months.

In this period, people at kilometer 19 called me saying, “we will leave on Wednesday or Thursday,” at that time in December.

But we heard news that they were arresting people on the water, that the [coast] guard was on the water with tons of boats, and no one was able to pass. There were two or three groups that they arrested, and they left them in Libya in the desert and that. So I said that I wouldn’t take the risk.

Finally on the water

The Arab [organizer] kept saying, “I’ll send you off soon, I’ll send you off tomorrow,” again and again and again.

He finally sent us off in February. We started the engine, and they sent us off. When we were on our way, the people who had organized it had put around 70 people on the boat. When we were that many in the boat, the boat punctured. There was a bang, and we saw that we started taking in water into the boat.

We were like this, the water was here, and we were here [gestures the water height in the boat]. Almost under water, we were close to capsizing. We were barely able to stay there, and could barely run the engine.

The [coast] guard arrived, “my friend, it’s over, hand over the engine, it’s over.”

They took the engine, how did they take the engine? They wanted to shoot us, [they pointed at us] as if they were going to shoot us. As if they wanted to shoot at us, while we were capsizing. I don’t even know how I’m still alive. We were just there like that. I told myself, “shit, this is really great.”

We began praying. The Muslims started praying, prayers from the Quran, like that.

…

They pushed us away into the middle of the water, and there were cameras. The cameras were filming us, and they were asking questions. We were saying please, please, excuse us, we’re not going anywhere, please.

When they made the water go like that [purposefully making waves], and it was like they wanted to kill us, we cried out, we cried. Finally, they called the [rescue] boat.

…

I arrived at the port, and it was very difficult. That’s when they were going to take everyone to the desert. But me, with my bad health, they left me alone. They left me alone because of my health, with the young Ivorian who was with me. They left those who were sick, and pregnant women.

After being left alone at the docks while all the rest of her groups were taken to the border with Libya to be dumped in the desert, Nelle spends some time with a contact in Sousse and comes back to Sfax for another attempt right after Ramadan. That would be in mid-April 2024, about a month before our interview.

The second part of this interview will start there.