#9: Hasta la vista, ya Tunis

Diplomats are doing the most, lawyer is working on overtime, and the journalist wonders: Will I ever make it out? Then, one morning: "The case is closed."

NOTE: This is a continuation of a previous episode. For full context, please find the previous episodes here. If you’re reading the School of Tunisia for the first time, you can find an introduction to the page here.

On one of those late-November or early-December days, I went looking online for a good audio recording app for my phone. It’s one of those things you don’t write down in your notes, so I cannot recall the exact date. However, I had been meaning to get it done for a while.

I double-checked that my VPN was on and started googling. I wanted to download an audio recording app that could record sound in the background without showing up in my phone notifications. I was scared what would happen when I eventually went to the airport to try to travel, knowing that I’d be going through a police check without access to my lawyer. Would they take advantage of the opportunity to get me one-on-one? Would they search my things? Confiscate my external hard drive, my cameras or my computer? Try to search through my phone? The least I could do was to document it with an audio recording.

I found a suitable app, downloaded it and tested it. It provoked immense anxiety, but it worked.

On November 30th, I updated my lawyer with the information that Lars Løkke Rasmussen and Mohamed Ali Nafti, respectively the Danish and Tunisian foreign minister, would be meeting on December 2nd, and that the Danish minister would bring up my case. He confirmed reception of the message and told me that he would be checking in at the Administrative Court the following week and hopefully find time to go to Sfax as well.

The ministerial meeting meeting took place in Egypt on the sidelines of the Cairo Ministerial Conference to Enhance Humanitarian Response in Gaza on Monday, December 2nd. The day after, I got an update from the Danish ambassador in Algeria regarding the meeting.

In my December 3rd notes, I wrote:

It's crazy that we have reached December, and that this still has not been resolved. I've never felt nearly this cynical and jaded about the world. I guess there are good news today, though it's honestly difficult for me to get excited. It just feels like they're playing their stupid little games that result in nothing positive or serious at the end of the day and that all in all amounts to glorified cosplay for no good reason other than to feel official and important. The good news is that Katrine [the ambassador] sent me a WhatsApp message in the early afternoon mentioning that the Danish minister of foreign affairs, Lars Løkke, met with the Tunisian minister of foreign affairs and brought up my case. Apparently the Tunisian MFA didn't promise anything but said he would look into the case. Katrine said, "Så er der lagt maks pres på," meaning this is the maximal amount of pressure. I'm not sure if that's true, or at least it might not be the whole picture, as I'd imagine there are different types of pressure. I mean, heavier pressure could be to threaten to delay the embassy opening, for example. Not that they'd do that. But still.

As you can tell from this mood snapshot, I was not feeling happy. I had gotten my hopes up too many times in vain - the boy, the Danes, the Tunisians, the system, my lawyer had all cried wolf too many times, and I didn’t believe it anymore.

I spoke with my lawyer that same day. He was planning to visit the Administrative Court the next day, Wednesday, December 4th, to see if they had approved my request for suspension of execution of the S17, and go to the court in Sfax Friday.

Nightmares

As planned, my lawyer checked the status of my case at the Administrative Court. Nothing new. At this point, it had taken a judge at the court more than three months to consider if they should temporarily suspend the S17 procedure levied against me, and still, there was no decision. Don’t forget that the same court has previously declared the S17 an illegal practice across the board.

But surprise had ceased to be part of my emotional response register.

I was told, however, that once the case at the court in Sfax was closed, we could present the court with an official certificate of case closure, which might help convince the judge to put a stop to this illegal practice. Cool.

I then awaited the next trip to Sfax.

The following two nights were awful. I’m sure this was triggered by the anticipation of my lawyer’s trip to Sfax Friday two days later, combined with my fear of missing the wedding in Nepal.

I went to bed Wednesday night with no ability to sleep. I was in between crying, feeling deeply hopeless and being so angry that I felt like I had to throw up a physical pit of anger stuck somewhere between my chest and my stomach. Thursday morning, I was planning to attend a conference at a local university where a friend of mine was speaking. But when I ‘woke up’ from my girlfriend’s alarm, I felt like I was still waiting to fall asleep from the night before.

Wednesday night was bad, but Thursday night was worse. I was exhausted from the lack of sleep the night before and went to bed early. However, at 3 a.m., I woke up from a nightmare.

This was the only time during the seven months that I wrote down one of my dreams in my daily notes:

I dreamt that there was a knock on the door to our apartment, which I opened, and a police officer stood there (in civilian attire of course) with a phone by his face, screen facing upwards so the phone was horizontal, as if he was going to play audio from it. I thought that it was quite weird when he started speaking instead. But he did. He started with something like, "I have a message from the Tunisian police." I can't really remember all the details of what came after, but I thought, I'd better film this in order to have it for proof, so I took out my phone and started filming.

He continued to speak and told me something about new charges. Some of it related to translation of data. I remember it as somehow connected to the third of the three reasons for the investigation, which was about handling data without the data subject's consent.

He then said that it was about a Yemeni student, which I also found weird, because I've never spoken with a Yemeni student in Tunisia, or a Yemeni person full stop [in Tunisia,] I don't think.

Then he tried to grab my phone. It was as if he hadn't really realized I was filming until he finished his monologue. But I ripped the phone out of his hand and kept it back. Then he said something about "never really understanding these people who say ACAB" [meaning All Cops Are Bastards] which I honestly found a bit silly. But at the same time, given the seriousness of the situation, I told him that it wasn't about that, and I simply needed it so I could reference what he was saying to my lawyer.

Somehow that calmed him down, and after a few more words back and forward, he had been convinced that it was fine. Also very weird...

Well, then I finally asked him what this means in terms of me leaving the country. He told me that it means I have to stay in the country for at least 8 more months. That's when I screamed out in disbelief (in the dream) and woke up.

After that, I laid awake in bed until my girlfriend’s alarm went off in the morning. Then I slept for about an hour, until she came to say goodbye before leaving for work.

I reached out to my lawyer in the late afternoon to ask if he had managed to go to Sfax as planned, but didn’t receive a reply.

Over the weekend, I didn’t hear any further updates. I carried around a lot of anger and was fantasizing about being rude to the airport police on my way out. One particular thing was on my mind: Since my residency expired back in September, I was now overstaying my visa by nearly three months.

In Tunisia, overstaying your visa can be handled in a very simple way. You simply book your travel out and pay an overstay fee of 20 dinars (around US$ 7) per week you’ve overstayed when you get to the airport.

The prospect of paying for my ‘overstay’ felt like the gravest, most humiliating insult of them all. That weekend, I was playing out every possible scenario of refusing to pay in my head, resulting in a negative anger-spiral that left me tense, on edge and willing to sacrifice myself to make them hurt. It was not a good place to be.

Finally, on Monday morning, I received a message from my lawyer who apologized and told me he had fallen ill the previous Thursday. He told me he had court proceedings the following two days, but that Thursday, December 12th, he would go to Sfax, no matter what. “Even if he was in a wheelchair,” he said.

The final trip to Sfax

On Tuesday, December 10th, we were officially 10 days out from the wedding in Nepal. My girlfriend had booked refundable tickets a couple of weeks before, but the odds were still stacked against me. Even if my lawyer were to return from the court in Sfax that Thursday with news that the case had closed, I’d still have to get out of Tunisia with an active S17 against me.

That afternoon, I was scrolling Facebook when I found a new legal guide for journalists to know their rights in case of arrest, published by the National Syndicate of Tunisian Journalists (SNJT).

Among other things, the guide explains what a legal arrest should look like. It also includes a list of 13 shortcomings that are often seen in cases of arrests of journalists in Tunisia. Out of the 13, I was subjected to eight, and with regards to a couple of these points, I was subjected to worse than the guide warned of:

Lack of information on the objective of a convocation: It constitutes a breach of the right to proper legal defense to not specify the objective of a convocation. This happened to me multiple times.

Failure to inform the journalist of their rights before appearance or detention: It’s required by Tunisian law that in case of arrest, the police must inform the suspect that they’ve been arrested, why they’ve been arrested and what their rights are. I not only experienced a lack of information, but also active withholding of information regarding my rights when I requested it.

Pressure to not have a lawyer: As Wifak was attempting to get a hold of a lawyer in the police car’s backseat, the officers repeatedly ordered her to put her phone away. If she had not defied their orders, no legal assistance would have shown up on the night of our arrest in Sfax. Furthermore, our lawyer was physically prevented from entering the interrogation room during one of the two interrogations that night.

Long duration of waiting or appearance: Long waiting times contradict the right to an equitable process and can constitute a form of ill-treatment or moral torture, which can even justify a complaint over or cancellation of the procedure. Most notable, in my case, is the de facto sleep deprivation between the day of our arrest and our court appearance the following day, when we were let go past 2 a.m. with an order to appear at 9 a.m., but were made wait for several hours at the police station for no reason before we were escorted to the court past noon.

Too short of a period between convocation and appearance in front of the investigator: “This too short of a period, sometimes even for a convocation on the same day, goes against the right to defense and international norms concerning reasonable waiting periods," reads the guide. We indeed did receive one same-day convocation and another next-day convocation to appear in a city three hours away.

Interrogation of foreign journalists without a translator: Shockingly, the police station in Sfax was the only case in which this was done correctly.

Refusal by the prosecutor to accept the presence of a lawyer during the appearance after the end of the first period of detention: The suspect has a right to have a lawyer present during interrogations as well as during the first appearance in front of the public prosecutor. When I appeared in front of Liweddine Friji in Sfax, I was told that it is the “normal practice” in the court in Sfax to not allow a lawyer to be present for this. I couldn’t believe it at the time, but the lawyer assisting Wifak and I there agreed with the assertion. I didn’t realize until I read the SNJT guide on December 10th that this was a breach of my rights.

Interrogation of journalists by non-specialized teams: It’s problematic for investigators who are not specialized in media affairs to interrogate journalists. Of course, in my case, I was not even told who was interrogating me in the first place. Heck, I wasn’t even informed that I was under arrest. If they were indeed specialized in media affairs, then the Tunisian Ministry of Interior needs to urgently improve their media affairs training.

The SNJT-guide really put things into perspective for me. It made me realize that my case wasn’t just serious compared to how foreign journalists are usually treated in Tunisia - it was also bad in comparison with how Tunisian journalists are treated.

The next day, Wednesday, I woke up shortly before noon to a missed good morning-message from my lawyer. I responded, feeling bummed to have missed my chance to chat. However, no more than 20 minutes later, he responded.

He had left for Sfax early that morning - a day earlier than anticipated - since more work had come up for Thursday.

12:17 p.m. on Wednesday, December 11th, the message arrived: The case is closed. This implied that the S08 judicial travel ban had zero legs left to stand on. My lawyer was now waiting at the court for them to produce three copies of the certificate of case closure - two for the Administrative Court and one for me to bring to the airport.

I immediately reached out to my parents, the Danish embassy and my girlfriend and began looking at flights. The S17 was still there, and it would probably stay. I’d just have to attempt to travel and see how it would go.

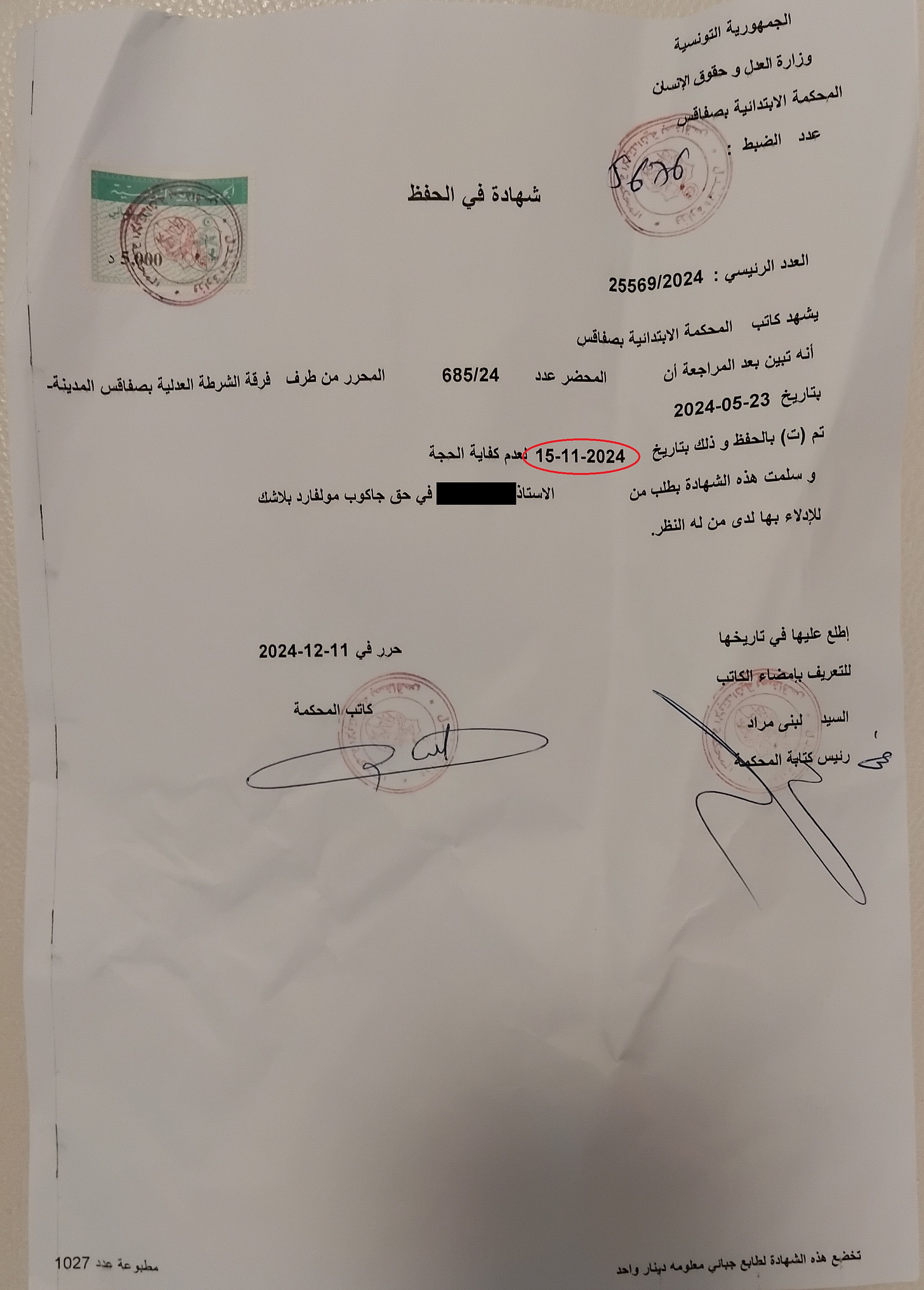

A bit before 6 p.m., I received a picture of the certificate of case closure.

Bizarrely, the closure date on the official document is November 15th, 2024. However, when my lawyer checked in on November 20th, he was told that the case was still open. Apparently, the court either found it relevant to fake an early case closure date, or they lied to my lawyer when he inquired on November 20th. I’m not sure why. Were they for some reason determined to keep the processing time below six months? Were they covering up the influence on the case closure exerted by the Tunisian Ministry of Foreign Affairs after their two high-level meetings with the Danish secretary of state and foreign minister?

I guess the only people who know are the people who work in that court. I doubt I’ll ever get the answer. And to be honest, that day, I did not care. Most importantly, the case was closed.

The last days

On Thursday, December 12th, I spent the day on the phone with my mom looking at flights. Without access to my own money since my cards expired in the summer, it was the only way for me to leave Tunisia.

We booked the flights and managed to match my outgoing flight to Nepal with my girlfriend’s flights so that we could travel together. I would be flying to Kathmandu, Nepal through Doha, Qatar, leaving Tunis at 4 p.m. on Tuesday, December 17th - just five days later. Then we booked another flight from Kathmandu to Copenhagen, Denmark, on December 26th - and at long last, I would have my freedom.

As I wrote in my notes that evening:

I really need all this to work out, I will be so fucked emotionally if they don't let me get on this plane.

Things went extremely fast over the next few days. Friday morning, I dropped off my bicycle with a private courier who drives a van back and forth between Tunisia and Scandinavia. I had also started playing in a Latin band in November, and we were playing a concert at a big event that evening, as well as the following Monday for the opening of the Carthage Film Festival. They were cool events, and being in the band allowed me to have at least one aspect of my life not revolve about my case.

Saturday morning, I went to an event hosted by the Tunisian Forum for Social and Economic Rights, in part to see some friends for the last time before leaving. I completely forgot that I was meeting with my lawyer that afternoon to chat and exchange legal fees. Thankfully, I remembered in the last minute, got a motorcycle taxi and managed to catch him on his way out of the office.

My lawyer confirmed that he would be presenting one of the certificates of case closure to the Administrative Court Monday, but that they would not be making a decision then and there. Thus, it was confirmed. I would be attempting to leave with the S17 against me still active. But with the case closed and the certificate in hand, most likely they’d let me through, I was told.

We also discussed what to do at the airport. They’d probably pull me aside in passport control due to the S17, leave me sitting for a bit, and then let me go. If they were to cause trouble, it might be because their systems hadn’t been updated, in which case I should present the certificate of case closure. For anything beyond that, I should reach for consular and legal assistance from the Danish honorary consul and/or my lawyer. And lastly, I had to make sure to show up early for the flight.

Sunday, I packed all day and finished most of it - though I had to pack around a large rectangular space in my suitcase reserved for my trumpet, which I would need for the concert Monday night. In the evening, I confirmed another meeting with my lawyer to exchange the certificates of case closure.

Monday, everything went as planned, and I got my certificate of case closure to bring to the airport. Later in the afternoon, my lawyer confirmed that he submitted the other two certificates of case closure at the Administrative Court as part of my lawsuit there against the Ministry of Interior. Before heading out for my evening concert, I emailed the Danes my last updates and the exact details of the flight I’d be on - if all were to go well.

We played a beautiful concert on Avenue Habib Bourguiba that evening - a truly cathartic ending to it all, miked up and with a massive audience. It was fun.

I also couldn’t help but feel a sense of satisfaction, as I was standing there on stage in the middle of the grand avenue I had come to dread so much because of its ridiculous police presence. I felt as if I was reasserting my right to be there - my right to exist. And with a trumpet in my hands and the music blasting, there was nothing they could do about it.

To leave or not to leave

After getting some dinner and heading home Monday evening, my girlfriend and I packed my trumpet and the last few things to get ready for my attempt to leave Tunisia the following morning.

We got up, Tuesday, December 17th, 2024, and got ready. Then we arrived at the airport at 10 a.m. for our 4 p.m. flight in order to leave plenty of time. Unfortunately, Qatar Airways didn’t open their bag drop until 1 p.m., so we wasted away three hours at the difficult-to-afford airport café.

After dropping our bags and heading towards security, my heart was pumping. My girlfriend and I walked together into the departures area and lined up for passport control. On the way in, I confirmed with my lawyer that I was headed in, and he let me know that he was ready to assist if need be.

At the very back of the line, I took a quick look around. No one was watching - not even my girlfriend. I took out my phone and discretely turned on my audio recording app.

After a 10-minute wait, we reached the front of the line, and my girlfriend and I presented our passports together at a booth. As expected, the computer flagged my passport, and we were told to follow a person over to the side of the large room - to the same rack of wall-bolted benches I had been seated on on June 25th, during my last visit to Tunis-Carthage International Airport six months prior.

My girlfriend was told she didn’t have to come, but she came anyway, and no one seemed to mind.

A man in his late 30s wearing jeans and a dark-red suit jacket appeared, donning a haircut that laid somewhere between a fade and a tiny mohawk, resembling that of a black pill podcaster. He came over to me and spoke in English with what I'd describe as an arrogant and irritated attitude towards me. I engaged politely.

He asked if i was a resident, and I told him that I used to be, but that my residency had expired. He asked annoyedly for my residency card, which I gave to him. He then walked off before I had a chance to say anything else.

After waiting for a bit, I texted my lawyer an update, and he asked if I had shown them the certificate of case closure, which I had placed at the very top of my hand luggage to be prepared. I told him no. He told me to try to politely go up to the man and tell him that this might be an important document to consult, and that my lawyer could be present in 30 minutes if they needed further explanation.

Sitting on the bench there, one is left in uncertainty regarding whether or not one is allowed to even stand up. So I tried for a bit to get the man’s attention, but he was aggressively and deliberately avoiding eye contact. Eventually, I spoke up as he walked past and said "Sir, excuse me."

Saying it pretty loudly, he stopped. I walked up to him.

“I think this might be important, too,” I told him and handed him the certificate of case closure. “And I should add that if you need more explanation, my lawyer can be here in 30 minutes,” I added.

“I don’t speak English,” he responded in great English.

“What?” I said confused.

“I don’t speak English,” he said. “Parler français” - “speak French!”

“I don’t speak French,” I responded back.

He handed me back the certificate of case closure - which, as we saw above, is in Arabic - without looking at it once.

“You want me to take it back? You don’t want to see it?” I asked him.

“Sit, sit!” one of his collegues yelled at me in annoyance and pointed back to the rack of chairs. Back I went.

The exchange sounds both ridiculous and, frankly, difficult to believe, so I’m attaching the audio clip below:

Back in my seat, I informed my lawyer what had happened. My lawyer had me reach out to the Danish honorary consul as well about the situation, and he asked me if I had any way of catching a later flight if I missed this one. At this point, a bit less than two hours remained before our flight was scheduled to depart. I replied that yes, in principle I could get a new flight, but it would be difficult to buy it because of my lack of access to my bank account.

I was made to understand that my lawyer was getting ready to leave his office to assist. He went directly to the police station with the Administration for Foreigners and Borders to deal with them there. My guess was that he didn’t go to the airport because, considering their uncooperative attitudes, he’d expect them to shoo him over there anyway instead of dealing with the situation at the airport.

I believe that his primary purpose there was to make them understand the situation - that I had had an investigation against me, but that it was now closed.

Not long after my lawyer told me he had arrived at the Administration for Foreigners and Borders, another man came over to me on the airport bench. He was wearing a white button-down shirt and a much friendlier demeanor. He held up my passport and asked if it was mine. I confirmed.

Then he took my passport into the office to the immediate left of the bench rack. I could see that he and his colleague started entering information into the computer from my passport, so I figured that something was finally happening. My girlfriend made the guess that the passport had probably just been sitting on a desk in a back room all this time, and I wouldn’t be surprised if she was right.

The black pill cop passed by one last time, still pretending like I didn’t exist even though I had started eyeing him down aggressively. It seemed like he was getting his things and ending his shift. I assumed that he was off my case.

With a bit less than an hour to go before our flight left, the cop in the white shirt came back with my passport and expired residency card. He asked us to follow him. We walked back to the stamp booth again, and a man took my passport and started filling out a form on his computer. Finally, they stamped the passport and let us continue.

Was this real? Were we through? Not even a request to pay the overstay fee? At that moment, I didn’t believe it. And I didn’t have much time to either, because the plane was about to board, and we had to get to the gate.

We boarded successfully.

Sitting on the plane, my girlfriend asked me how I felt.

“I’m not going to believe it, until the plane is in the air,” I told her.

After a decent plane dinner and a handful of hours, we found ourselves at a luggage scanner in the airport in Doha. My carry-on bag had every electronic device and charging cable I own in it, so of course the scanner flagged it.

An airport security officer brought me over and greeted me.

“Don’t worry about it at all, there’s just a lot of wires in there, and the machine couldn’t figure it out,” he said to me with a smile.

He quickly swabbed the outside of my bag and put it in the explosive trace detection machine. The result was an immediate negative, of course.

The security officer told me I could grab my bag, and I thanked him.

“Safe travels, bro,” he added.

I walked off with a smile. It was really that easy.

This was the final episode of my story of being subject to seven months of political persecution, arbitrary detention and criminal investigation because of my migration journalism in Tunisia. While the main storyline is ending with this post, I will be publishing at least one more post - part 2 of my interview with Nelle, to come next week.

If you found this post interesting and you’re interested in more, subscribe to this Substack to be alerted whenever the next post is published.